Fifteen years ago, I bought my first home and started my first garden. Since then I’ve interned at the Dallas Arboretum, worked as a greenhouse plant propagator, held leadership roles at two community gardens, and completed the training to become a Certified Texas Master Gardener.

Though I love my current home and gardens, there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t dream of my next landscape and what I would do with it.

Knowing what I know now, if I had to start a garden from scratch…

I would…

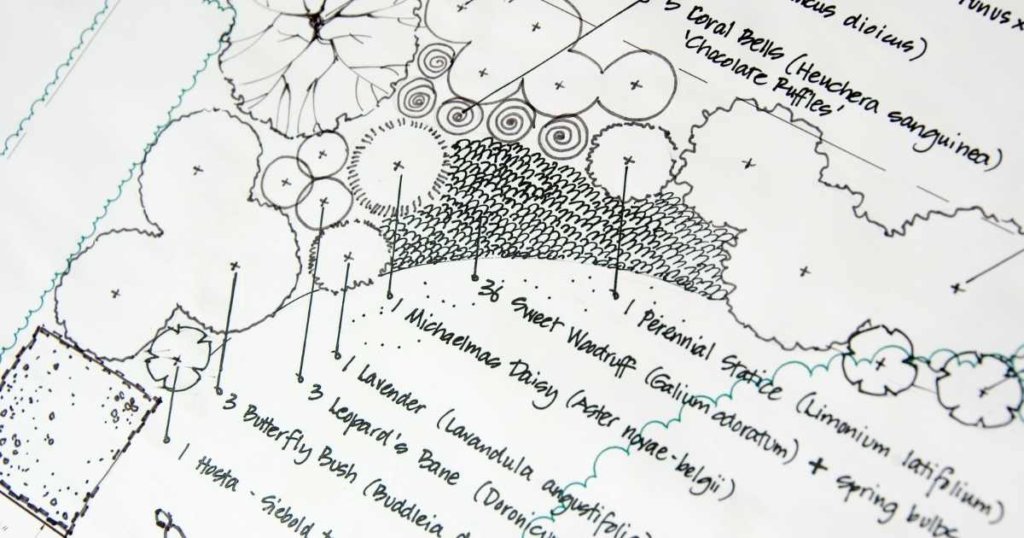

1. Create a master plan

The best looking landscapes are well-planned. Even landscapes intended to look completely natural will look more pleasing to the eye and the senses when it has been thoughtfully and intentionally planned out in advance.

A well-planned landscape achieves many things including:

- Harmony with the seasons.

Planning a landscape is more than its layout and structure. A good garden plan also accounts for seasonality. For example, a tree can look completely different in fall than it will look in summer. Flowering perennials are much the same.

When selecting plants for a landscape plan, avoid planting a garden that contains only summer-flowering plants, leaving the garden devoid of color in the spring and autumn. - A sense of flow and movement.

Part of my landscape design education included the study of Japanese gardens and the principles behind them. An important element of formal Japanese gardens is the idea of “hide and reveal”, also known as “miegakure”.

Miegakure suggests that every garden should have an air of mystery that draws the viewer in and creates a sensation of the garden unfolding as one moves through it. This is accomplished by partially obscuring portions of the garden from the viewer using winding pathways, plant screens, gateways, and other physical barriers.

Movement in a garden can also be created through repetition. A dramatic example of repetition in a Western garden might be a long driveway flanked by rows of tall, Italian cypress. - A lifestyle for the user.

The best diet plan is one that you will follow, and the best garden is one that you will actually use. There is no point in building vegetable gardens if you hate eating vegetables, and there is no point in planting salvias if you hate the color purple.

At the end of the day, your master garden plan should answer the question, “What do I really want and what will I really use?”

For me, my garden must have: 1) a space for guests to gather (I love entertaining), 2) dramatic plants (read: jaw-dropping agaves), and 3) plenty of space for vegetables.

2. Build a minimum of 6 raised beds

Growing vegetables in raised beds not only improves drainage, but it creates a bit of order in the garden. As we know, vegetable gardens don’t always look neat and tidy, especially at the end of a season.

The problem with raised beds is that we tend to build too few of them, and we limit the amount of food that can be grown and the types of plants that we can try. Building more raised beds also allows us to dedicated an entire bed to one crop. This makes our gardening much more efficient (see How to Garden Like A Farmer).

I love when an entire bed is dedicated to one plant. This fall, I have 40 feet of row space just for tomatoes, 20 feet of row space just for winter squash, and 20 feet of row space just for cauliflower. It has dramatically reduced the amount of time I spend in the garden each morning because I’m not switching between hose attachments or

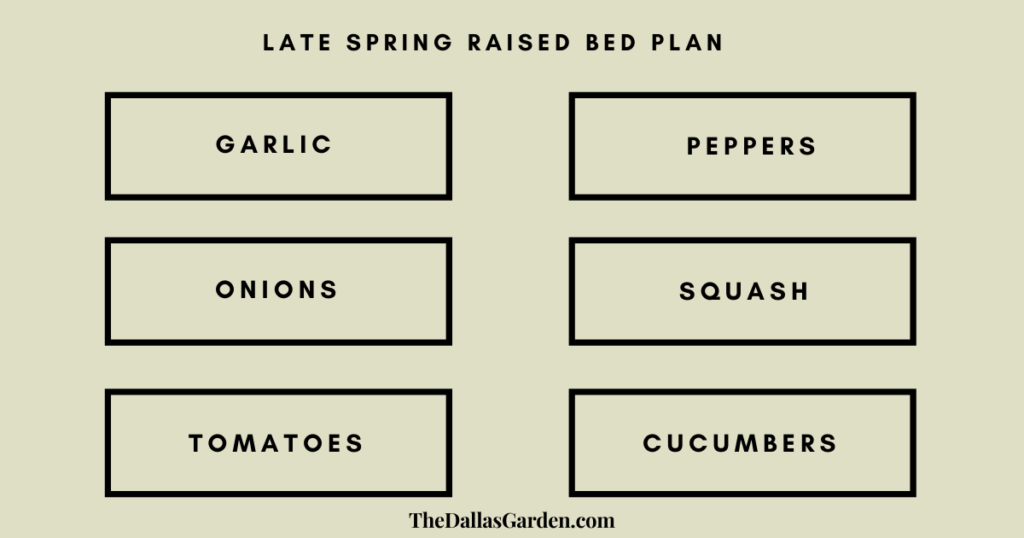

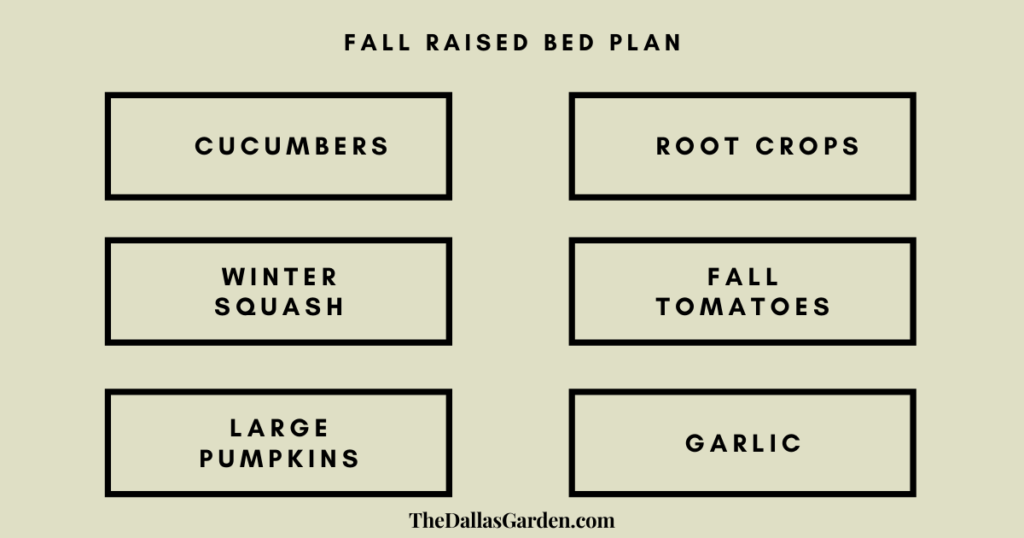

Why six beds?

Six beds gives us enough space to grow a large amount of food each season, and leave a few beds available for mid-season crops like garlic, for example.

In North Texas, garlic is planted in mid-October. If we only had two or three raised beds, they would all be filled with our fall crops by this point in the year, leaving us no room for planting the garlic. Onions are another example. Planted in late January, onions will still be in the ground by the beginning of June, way past the time that spring crops should be planted.

Here is an example of how I would plant six raised beds in my “from-scratch” garden:

3. Construct shorter raised beds

(Forgive me while I step up on my soapbox…) The worst trend I see in gardens today is raised beds that are too tall. The only reason that a raised bed should be taller than 12 inches off the ground is if there is a physical limitation of the gardener preventing them from working a garden bed that is close to the ground. That’s it!

Why tall raised beds are so bad

Raised beds have two benefits 1) better drainage and 2) better soil because you can control the soil in the beds. But raised beds are not perfect. In fact, raised beds can cause MORE problems than they solve when they are too high.

They expose the soil to high temperatures.

Beds that are too high are especially dangerous in our area where summer temperatures regularly soar above 100 degrees. This is because they expose the soil to the ambient temperatures. This dramatically raises soil temperatures, and vegetables really don’t like this. High soil temperatures cause plants to suffer extreme stress. This stress can stop fruiting altogether and increase a plant’s susceptibility to pests and disease.

Tall beds dry out quickly.

A tall raised bed in the middle of summer can require twice daily

In short, when it comes to tall beds, don’t do it!

Benefits of short raised beds (12″ maximum):

- Plant root systems are kept cool because they can reach into the ground soil beneath the raised bed.

- Moisture retention is much higher and much less water is needed, saving you money on your water bill.

- Higher nutrients and fertility. Our native soil isn’t terrible. In fact, black clay is higher in nutrients than other soil types. It is the texture of our soil that is challenging. Because of the clay content, our soil doesn’t allow roots to penetrate because there are no air pockets. Raised beds will improve the drainage, but keeping them short will allow the plants to access some of the nutrients and fertility that naturally occurs in our soil.

4. Fill raised beds with a 50/50 soil blend

When I built my current raised beds, I found a local bulk supplier advertising a “Veggie Mix” that was touted as the perfect mix for raised vegetable gardens. I paid a pretty penny to have it delivered and then spent eight, back-breaking hours moving it one wheelbarrow at a time into the beds. Three months later, every single vegetable I transplanted into it had yellowed, withered and died.

It was an expensive, and heartbreaking lesson in the danger of trusting shiny marketing.

The best mix for vegetables

This year, my father found a different supplier offering a 50/50 blend of topsoil and compost. As unsexy as it sounds, this mix turned out to be the best soil mix I’ve ever seen in my 15 years of gardening. Every single plant that my father put into that soil grew over six feet in height (even the eggplant!) and produced more vegetables than I had managed to grow in two years at the same community garden. It was nothing short of spectacular.

A 50/50 blend of topsoil and compost is also recommended by our local Agrilife office.

Avoid commercial bagged raised bed mixes

In another Dallas community garden where I have volunteered, several of the raised beds were filled with Kellogg brand Raised Bed Soil Mix. To our horror, we discovered that the mix is mostly shredded wood, which explained the low price point.

Shredded wood in large amounts is very bad in a soil mix. This is because that wood will continue to try and break itself down. This process of decomposition requires nitrogen. And where does that nitrogen come from? It gets pulled from the soil and away from your plants.

5. Leave only enough turf to generate compost

You might be surprised that I wouldn’t remove all of the turf in my landscape entirely. While I firmly believe that landscapes with excessive turf are not good for our environment because of water usage, gas pollution, and chemical applications, I do believe in grass for its potential as a “green manure”.

Grass clippings are one of the best materials for composting. It’s already shredded, so it breaks down quickly. And it is a superb source of nitrogen.

If I were to start a garden from scratch, I would definitely make sure to maintain a small area of grass to make clippings. My preference for turf would be St. Augustine.

6. Grow more of less

If I were starting my garden again from scratch, I would focus on fewer plants and just plant more of them.

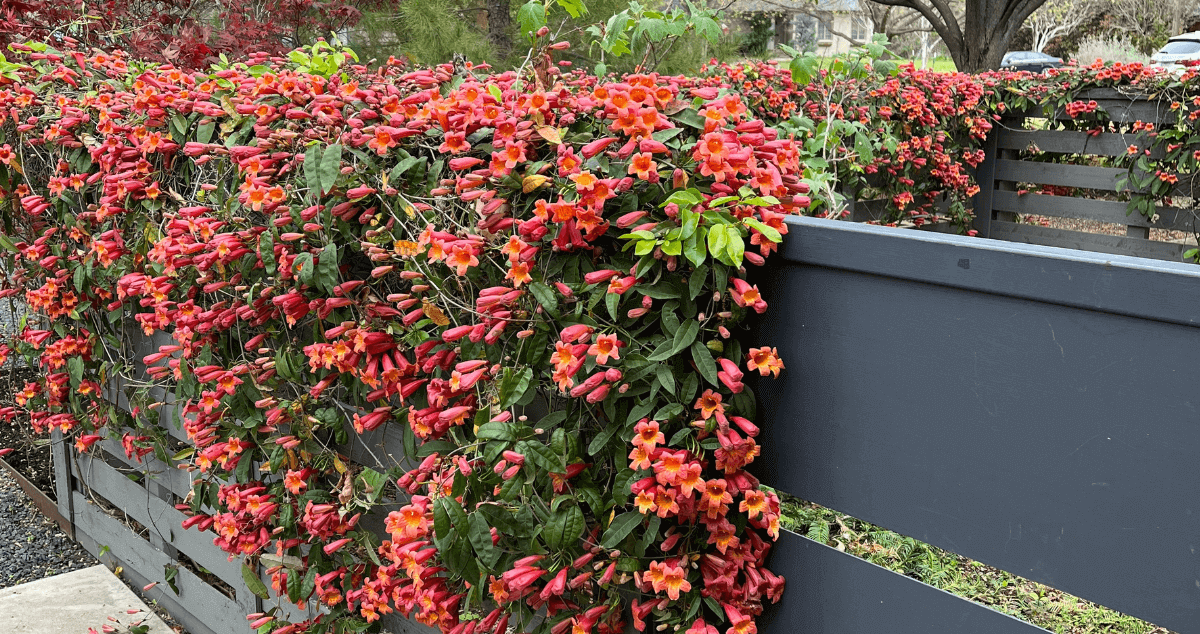

Plant in mass

One of the most important concepts of landscape design that I try to instill in my students is the idea of planting in mass. Instead of buying and planting one of everything, reduce your plant selection to a few plants and then buy heavily into each of them and plant your landscape in swaths of plants.

This technique results in landscapes with intentionality and dramatically more impact because it gives the eye a place to rest. Instead of darting from one color to the next, one plant to the next, the eye is drawn slowly into each plant “swath” where it can fully take in the glory and the impact of each plant. (Think about your last visit to the Dallas Arboertum during spring tulip bloom.)

Get more bang for your buck in the vegetable garden

This was one of the first years that I made a commitment to growing more of fewer crops. In the spring I only grew garlic, onions, tomatoes, okra and peppers. That’s it! But, I grew a TON of them.

I grew 24 tomato plants, 120 garlic plants, 200+ onions, 6 okra plants, and 6 pepper plants. Despite the narrow selection, I produced the highest yield of vegetables in my 15-year growing history. It allowed me to donate the majority of it to a food pantry and give the rest away to family and friends.

Growing more of less is a garden best-practice because:

- It saves you time.

Just like a factory-worker who specializes in one task, growing more of one plant makes you faster in the garden because your using the samewatering methods, same fertilizers, and same harvesting pattern. - It saves you money.

Growing more of less allows you to purchase in bulk. When I order garlic, I purchase a “variety pack” of eight different kinds of garlic, and save 15% off the price of purchasing each variety individually. The same economies of scale apply to my onion plant purchase. Dixondale Farm offers a quantity discount. If I order one bunch of Superstar onions, I pay $12.35 per bunch. But if I add two more bunches to my order, I pay just $7.30 per bunch.

7. Build in dedicated spaces for annuals

I used to be so focused on growing vegetables and pollinator perennials (plants I saw as purposeful) that thought of annuals as a waste of my time and money.

But now I have several containers around my home dedicated to seasonal annuals, and the practice of refreshing them throughout the year fills me with excitement. Planning the combinations of colors and textures feels like creating a piece of art.

Though planting vegetables and perennials can make us feel like we’re doing something good, annuals are just as important for creating a balanced landscape.

If I were starting from scratch I’d design perennials beds with dedicated space for annuals, and maybe even add some “window boxes” to my raised beds where annuals can keep the vegetables company.

8. Blend natural and formal

If I were starting my garden from scratch, I’d build in some more formal elements. I’m partial to a natural, relaxed landscape, but I’ve fallen back in love with the formal elegance of English gardens. The British have such a rich traditional of gardening that I can slowly see being adopted in the states. Perhaps some of the formality will rub off as well.

Formality can be added to be a garden with more than just plants. Hardscaping with tiled, bricked, or stone pathways can provide formality as can short walls, gates, doors, trellises, archways.

- Gardening Gifts That Mom Will Love - May 7, 2024

- New Plant I’m Testing: Kitchen Minis™ Bonsai Basil - April 24, 2024

- Resilient Perennials I’m Adding to My New Landscape - February 28, 2024